Read an extract of my free e-book below, then download the full dastardly dictionary here.

Mr Dickens’s Dreadful Dictionary

This is Mr Dickens’s compendium of murder –a dictionary of atrocious acts, dreadful deeds, and hideous horrors. Dickens asks the question:

‘Is it in the interest of any man to steal, to gamble, to waste his health and mental faculties by drunkenness, to lie, forswear himself, indulge hatred, seek desperate revenge, or do murder? No. All these are roads to ruin. And why do men tread them? Because such inclinations are among the vicious qualities of mankind.’

Dickens might have added why do women tread them? There are plenty of murderous women in the annals of Victorian murder. Whether committed by man or woman, it does seem that real murder took hold of the imagination of Charles Dickens.

There are all kinds of murders in the novels – and murderers, including a woman. And he was always reading about murder – that is clear from the number of references to notorious cases which appear in his letters and articles for his magazines.

A is for Arsenic

White Arsenic comes in the form of a white powder which has no taste – this renders it most dangerous. Alfred Swaine Taylor who is called the father of forensic science observes that ‘most of those persons who have been criminally or accidentally destroyed by arsenic have not been aware of any taste in taking the poison.’

Charles Dickens wrote an article about arsenic in his periodical Household Words. ‘It is clear’, he says; ‘that the favourite poison with us is arsenic’. He quotes from Alfred Swaine Taylor: ‘Doctor Taylor cites no less than 185 cases of poisoning by arsenic alone in England in the years 1837 to 1838.’ Dickens is writing in 1851 and he wonders how many more cases have come to light since. It wasn’t until 1851 that the sale of arsenic was regulated. The new law stated that arsenic should not be sold unless in the presence of a witness, all sales must be recorded and signed for by the purchaser; no arsenic should be sold without being mixed with soot or indigo. Dickens was very sceptical about the enforcement of these regulations and to prove his point that nobody attended to them he refers to a number of cases.

Mrs Barber and her paramour, Ingham, murdered her husband; Mrs Hathaway, landlady of the Fox beer house in Chipping Sodbury was murdered by her wastrel husband; a Mrs Dearlove – clearly she was not – was murdered by her servant girl, Ann Averment. A Mr and Mrs Waddington murdered their daughter for the sake of £7.00 from the burial club. Sarah Chesham murdered her husband – there was arsenic in every one.

And it wasn’t just the pretext of poisoning rats that made arsenic available so easily. Arsenite of copper was used as a food colouring – it was called Scheele’s Green. In a case which was the subject of a criminal trial, this deadly compound, as Dr Taylor calls it, was proved to have caused the death of a gentleman at a public dinner for arsenite of copper was used to impart a rich green colour to the blanc mange – I suppose one can see why – pink or white blancmange is not very appetising. The cook, incidentally, was convicted of manslaughter.

Murder was done by arsenic in a cake. Dr Taylor quotes the case of Rex V. Lofthouse where a wife, Ursula Lofthouse, murdered her husband, Robert, by means of a cake she said she had made especially – well she had, especially to kill him. The cake was laced with arsenic. Dr Taylor cites the case as an example of one in which the poison acted the victim in the very act of eating.

Arsenic was all over the place – in blancmange, in cakes, in buns, in bread – even on lampshades, and in wallpaper which was often covered in arsenite of copper – look what happened to Napoleon.

It was in paint, too, which brings me back to Dickens. In 1867 he was staying at an hotel in Glasgow. He wrote to his daughter, Mamie, that he was ‘taken so sick and faint that I had to leave the table.’ It turned out that the passage leading to his room was being painted ‘with a most horrible mixture of white lead and arsenic.’

B is for Bayham Street in Camden Town

B is for Bayham Street in Camden Town. There’s Buckingham Street and Bentinck Street, too – all places where Dickens lived at some time. No wonder Dickens was fascinated by murder – each of these streets is associated with murder. Doctor W.H. Crook was found murdered in a brick field in the Caledonian Road. His address was Bayham Street. His throat was cut and he lay in a pool of blood. And in a touch worthy of Dickens himself, a black and white curly dog was sitting at his feet. It barked at anyone who tried to come near.

And more throat cutting: Dickens lodged in Buckingham Street in 1834. In February, 1837, in Buckingham Street, John Bryant murdered his son, William, and then cut his own throat. John Bryant’s landlord was – very Dickensian – Mr Gosbee. The newspapers described in gory detail the death of John Birkenger who was ‘stretched out on the floor, weltering in his blood, his throat being cut in the most dreadful manner.’ This occurred in Doughty Street in 1829 where Dickens lived from 1837 – 1839, and in the same street the dead body of an infant was found in 1828.

In Bentinck Street where Dickens took lodgings in 1833, a policeman was shot dead in 1848 during the Chartist riots.

In 1832, Dickens had rooms in Cecil Street – another blood-stained thoroughfare. Captain Swyney of the 63rd Regiment fell upon his sword in the Roman fashion, and at number 18, one Thomas Davison hanged himself by fastening a piece of rope to the bedstead – while the balance of his mind was disturbed, so the newspapers reported.

And B is for Bacon

In 1850, Dickens began his periodical Household Words to which there was a supplement entitled The Household Narrative of Current Events in which were recorded, among other news, reports of crime and murder.

Dickens must have had a shock when he read of the murder of Mrs Catherine Bacon at Ordnance Terrace, Chatham in 1855. He had lived there as a boy from 1817 – 1821. Mrs Bacon lived at Ordnance Terrace from 1813 – perhaps he remembered her. Not a name you’d forget. She was murdered in her house. Her servant girl Elizabeth Laws was accused. Her contention was that two unknown men had entered the house and killed her mistress with a cleaver and stabbed Elizabeth in the throat before running away. All suspicion pointed to Miss Laws whose injury was not serious. She was tried, but acquitted, despite the considerable evidence against her.

On the servant girl’s bedside table there were two books: Othello – clearly not suitable to a girl with murderous thoughts, and The Arabian Nights – one of Charles Dickens’s favourite books as a child. I wonder what he thought of that!

Remember the dog that barked in the brick field? The cat’s miaow? Mrs Bacon had a cat for which she had put down a saucer of milk before she was hacked to death. The police found blood in the milk – a somewhat gruesome detail, but that’s the newspapers for you! What happened to the cat, I wonder?

C is for: Courvoisier, Francois Benjamin

He was the Swiss valet of Lord William Russell, third son of the Marquis of Tavistock and uncle to the future Prime Minister, Lord John Russell with whom Dickens dined on several occasions. Whether they talked of this brutal murder, we don’t know. On May 6th, 1840, Lord William was found with his throat cut in his bedroom at 14 Norfolk Street, Park Lane. The valet, Courvoisier, declared that the house had been burgled, and, indeed, there were signs that someone had been in and thrown about articles of furniture and ransacked drawers.

However, the police were convinced that it was an inside job. A search of the premises revealed gold coins and articles of gold and silver belonging to Lord William secreted under the pantry sink and behind a skirting board. Courvoisier confessed when articles of silver were discovered in the possession of a Frenchwoman who owned a hotel. He knew she would recognize him.

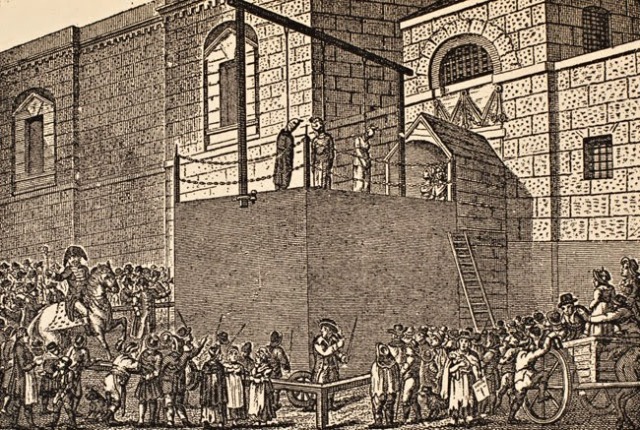

Courvoisier was convicted and hanged outside Newgate Gaol on July 6th, 1840. Public executions attracted large crowds. Those who could afford it hired upper rooms in houses overlooking the scaffold at a cost of between two shillings and sixpence and five pounds. The Examiner estimated that a crowd of 30,000 packed the streets, houses, pubs and shops to watch the terrible scene.

Dickens watched from an upper room – he was curious to see, he said, ‘the end of the drama’. No doubt he had a good view of the dreadful moment when, according to The Morning Post:

The death bell tolled. When they reached the door called ‘the debtors’ door’, which leads directly to the scaffold, Courvoisier shook hands with the sheriffs, the ordinary and several others, and walked up the steps in the most firm manner. The executioner soon put the rope round his neck and the cap over his eyes, and the ordinary had scarcely uttered ten words of the service when the light of this world closed forever on the murderer.

The Morning Post noted ‘the howls of execration from the crowd’. Dickens was sickened by the conduct of the crowd: ‘nothing but ribaldry, debauchery, drunkenness and flaunting vice’. His fellow novelist, Thackeray, was there, too, and felt ‘ashamed and degraded at the brutal curiosity that took me to that brutal sight.’

Dickens wrote that he was, in principle, against capital punishment. However, he knew that it would never be abolished and campaigned for the end of public hangings. His influence played an important part in the abolition of public hangings in 1868, two years before his death.

And here’s an interesting post script to the Courvoisier case. In 2012, a letter came up for auction. In May, 1840, Robert Blake Overton, a surgeon of Grimstone, Norfolk, wrote a letter to Lord John Russell after reading about the murder of Lord William Russell. The newspapers had reported the bloody handprints on the sheets. Overton’s letter advised that the marks be closely examined because, he wrote:

It is not generally known that every individual has a peculiar arrangement [on] the grain of the skin … I would strongly recommend the propriety of obtaining impressions from the fingers of the suspected individual and a comparison made with the marks on the sheets and pillows… The impressions made from the fingerprints of different persons will produce different shapes. He included examples of inky fingerprints to demonstrate his thesis.

His letter was passed to Scotland Yard. They took up Overton’s suggestion, but recorded on the back of the letter that the only marks were those made by the surgeons who had first examined the body.

The letter was found among 700 original documents relating to the investigation of the murder and subsequent trial. This obscure village surgeon was advocating the use of fingerprint evidence to identify the culprit fifty years before the procedure was adopted. In the 1850s in India, William Hershel experimented with fingerprints, but it was not until the 1890s that fingerprinting was used in criminal investigations.

What a pity that Charles Dickens did not see that letter – what might he contribute to the investigations of Superintendent Jones? Wait, though! Perhaps, he did see it … he had visited Norfolk … perhaps he met Doctor Overton. Perhaps, there is a new case to be solved: Fingers in Blood.